The Realities of Robot Deployment: What It Takes for Robots to Get Bought and Used

This perspective piece references a recent article on robot deployment and embodied AI: https://medium.com/dsaid-govtech/the-realities-of-robot-deployment-what-it-takes-for-embodied-ai-to-succeed-172a8f36fb2c

The article describes a pilot intended to assess the realities of deploying robots beyond controlled environments and closer to real world use. Its stated aim was to understand what it would take for embodied AI systems to succeed outside demonstrations.

Despite an intent to explore cost viability, the pilot relied on best in class robots and sensors that carry high cost by default. The lessons reported relate to operating robots in real environments, but they largely reflect challenges that are already well understood.

Many robots perform well in pilots and stall in practice, not because they lack capability, but because they do not fit naturally into everyday operations.

This pattern is not unusual. Robotics does not stall because robots cannot be made to work. It stalls because too few systems make sense to buy, deploy, and keep using once novelty wears off.

What follows focuses less on the details of that pilot and more on what experiences like it imply for how robots need to be built if they are to clear real buying decisions and remain in everyday use.

Designing for the World Robots Actually Operate In

Most robots are still designed around rigid, familiar forms. These forms perform well in structured, predictable settings. Many real environments are neither.

For example, infrastructure spaces, building voids, service corridors, and confined areas. Uneven, cluttered, and only partially known. Clearances vary. Surfaces degrade. Small obstacles are routine. Treating these conditions as edge cases forces complexity into sensing and control, increasing fragility and cost.

By contrast, some robots are designed to tolerate uncertainty physically. NIMBLER™ is one such example. Its deformable structure was chosen to maintain continuous contact and controlled interaction with irregular environments. Rather than abstracting away uncertainty, the form absorbs it mechanically.

This distinction matters. Systems that tolerate real conditions without constant tuning are easier to deploy repeatedly and easier to trust in everyday use.

Real environments do not make allowances. Neither should robots.

Excellence Emerges When Engineering Aims Higher Than Convenience

Much of mainstream robotics optimises for what is convenient to engineer. Rigid bodies are easier to model. Predictable motion is easier to control. Clean signals are easier to interpret.

These choices are understandable. They also tend to optimise for demonstration rather than endurance.

Engineering convenience optimises for demonstration. Endurance requires a different set of choices.

When engineering aims higher than convenience, different outcomes emerge. In the case of NIMBLER™, choosing a non rigid and deformable body meant that clean data, stable motion, and repeatable dynamics could no longer be assumed. Noise and irregularity became the baseline rather than the exception.

This reshaped how intelligence was designed. Algorithms were built to operate under noisy input and unpredictable movement, rather than to correct deviations from an ideal model. Control, perception, and decision making were developed together, each informed by the realities of the mechanical system.

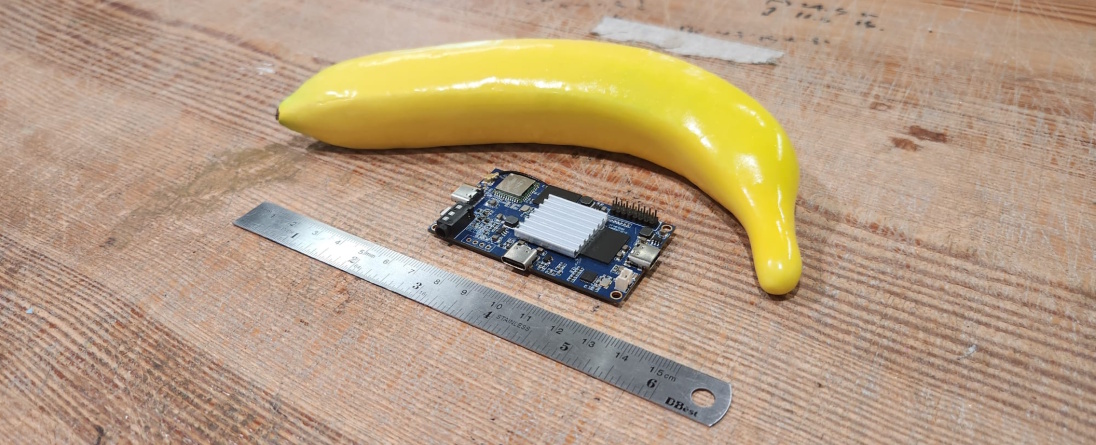

This shift extended beyond software. Dedicated computer hardware was developed alongside these algorithms, rather than relying on off the shelf compute platforms built around very different assumptions. By aligning mechanics, control, algorithms, and hardware, second order outcomes emerged. Energy consumption dropped. Hardware footprints shrank. System behaviour became simpler and more predictable.

Effective intelligence is not about adding more capability, but about aligning computation with physical reality.

These outcomes were not optimisation targets layered on afterward. They emerged because the system was designed as an integrated whole around the realities of the task.

This is not an argument for simpler robots. It is an argument for directing complexity toward real operating conditions rather than idealised ones. That is where engineering excellence tends to show up in practice.

Custom compute module. Created by MyrLabs. Banana used for scale, not image generation.

Robotics Has to Earn Its Place

Outside research environments, robotics is judged differently.

Automation competes with staffing, maintenance, and other operational priorities. Systems are evaluated on whether they solve a real problem consistently, whether they reduce friction, and whether they can be relied upon without exceptional handling.

Robots that only perform well under narrow conditions struggle to move beyond pilots. Even technically capable systems can stall if they are expensive to sustain, difficult to justify, or fragile in daily operation.

This is not a failure of imagination. It is how organisations function. Robotics succeeds when systems fit naturally into existing workflows and deliver value proportional to the task at hand.

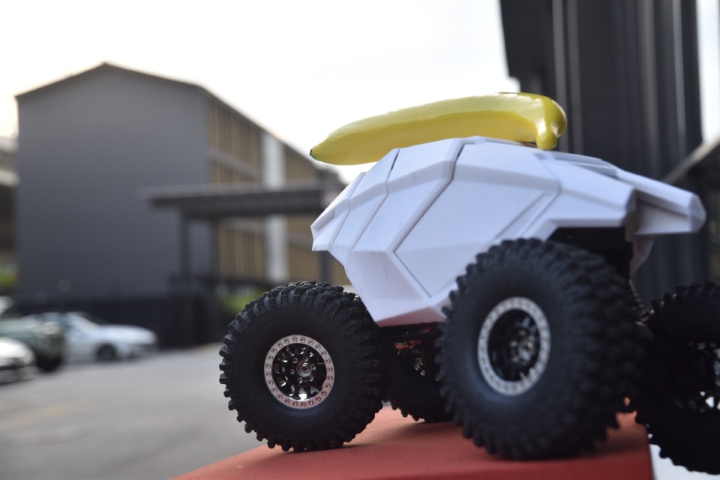

Little NIMBLER™ going into the dark

A Few Words on Home Grown, Private Enterprise Led Technologies

Across many small and open economies, there is a persistent tendency to undervalue home grown, private enterprise led technologies. Locally developed systems are often judged more narrowly, compared directly against global offerings on price or headline performance, and set aside quickly when they do not appear best in class on paper.

Home grown, private enterprise led technologies are often dismissed early because they do not appear best in class on paper.

This stance is usually framed as pragmatism. Imported technologies are seen as safer, more mature, or more immediately deployable. What is less examined are the longer term consequences of this reflex.

Private enterprise led development operates under a different set of pressures. These systems are built by teams that must deploy them, support them, and live with their economic outcomes over time. Design decisions are tested continuously against real operating conditions, cost constraints, and the need to remain viable without guarantees.

What is often overlooked is that sustained experimentation does not just refine existing approaches, it creates the conditions for entirely different solutions to emerge.

When home grown, private enterprise led efforts are overlooked early, these feedback loops are cut short. Local firms lose the opportunity to refine systems through real use, and the broader ecosystem loses the ability to compound capability over time. As a result, the ecosystem loses not only the potential for asymmetric wins, but also the conditions that allow unconventional thinking to surface solutions in unexpected ways.

Reliance on imported systems may appear efficient in the short term, particularly when global suppliers offer polished products and competitive pricing. But as dependence deepens, leverage erodes. Costs rise through upgrades, licensing, and integration, and the ability to adapt systems locally diminishes.

Reliance on external technologies can quietly turn economies into price takers, with costs rising over time without corresponding gains in capability.

Home grown, private enterprise led technologies follow a different trajectory. They may not lead on initial comparisons, but they preserve room for experimentation, substitution, and unexpected improvement. Some of the most meaningful advances emerge not from optimising existing approaches, but from constraints that force new ones.

In a multipolar world, the quiet dismissal of domestic enterprise capability carries real economic cost. Not because foreign technologies are inherently flawed, but because habitual reliance on them narrows options and forecloses the possibility of locally generated advantage.

Dismissing home grown, private enterprise led efforts early also means giving up the possibility of surprise wins that emerge from constraints, not benchmarks.

Seen this way, supporting home grown, private enterprise led technologies is not about preference or protection. It is about allowing capability to mature, retaining leverage over long term cost, and remaining open to outcomes that cannot be predicted in advance.

Conceptualized, designed, built, and proven in real environments in Singapore.

What Endures

Progress in robotics is not measured by how advanced a system appears in isolation. It is measured by how well that system fits into the environments, organisations, and constraints it enters.

Robots that endure tend to adapt quietly. They do their job without demanding constant attention. They make sense technically, operationally, and economically.

Those are the robots that get bought.

Those are the robots that get used.